Ending “Welfare As We Know It”: Redesigning Public Assistance through the Lens of Financial Health and Economic Mobility

Written by Reggie Bicha, Colorado Department of Human Services; Keri Batchelder, Colorado Department of Human ServicesIn 1996, President Clinton declared the “end of welfare as we know it.” The occasion was the signing of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), a response to the bipartisan call for welfare reform. This new law was intended to move people from “welfare to work” by restructuring federal public assistance and replacing the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. Initiated in 1935 as part of the New Deal, Aid to Dependent Children (ADC, later changed to AFDC) provided welfare payments to needy children from poor families, but by the 1990s, it failed to provide adequate focus or supports to help people move into employment, and it handcuffed generations of families to poverty. In contrast, TANF imposed greater restrictions on the disbursement of federal assistance, including a new 60-month lifetime limit on TANF benefits and work participation requirements.

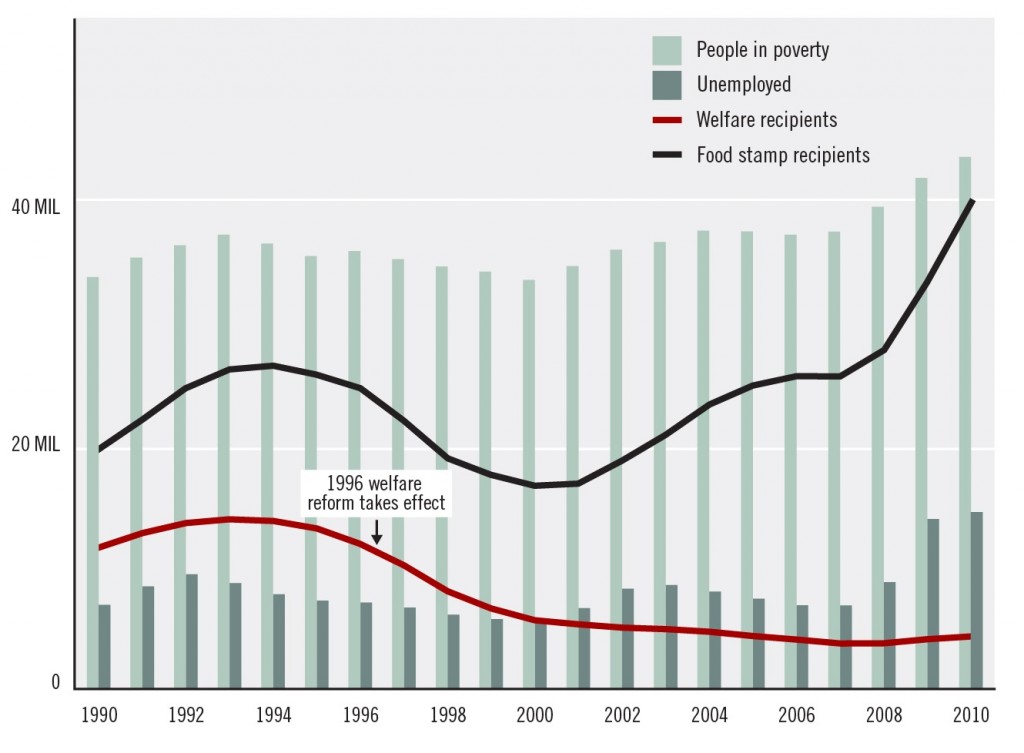

But did “ending welfare as we know it” adequately move America and its most vulnerable people forward? If the success of welfare reform is measured solely by the reduction in welfare caseloads, it was, unquestionably, a success (see Figure 1). Millions of Americans moved into the labor market, many for the first time. Childhood poverty rates initially declined. Yet, welfare reform also led to new problems and failed to resolve the economic mobility issues plaguing AFDC. America finds itself, nearly 20 years after welfare reform, with dramatically reduced welfare rolls and an increasing number of individuals in the workforce, yet significantly more children growing up in poor families.

Source: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Dept of Agriculture, Census, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Figure 1: Poverty and welfare in the United States

David Stoesz, a professor of social policy, conveys the predicament. “Welfare reform that offers the welfare-poor an opportunity to become the working poor,” he says, “is no real reform at all. The challenge that remains is to devise policies that will accelerate the upward mobility of welfare families so that they can partake in the American dream.”1 To do this, a new call to action is necessary, one that moves people from welfare to prosperity through work and asks the question, how must welfare policy be redesigned for the America of today?

Redesigning the System

A redesign of PRWORA and TANF requires a different emphasis, one that increases economic mobility and focuses on families’ financial health. In defining financial health, the Center for Financial Services Innovation suggests three core elements: day-to-day financial management; resilience to weather ups and downs; and long-term opportunity. These elements must compose the foundation of welfare redesign — a redesign that asks how is public assistance leveraged to build financial health, allowing people to move out of poverty and create opportunity for future generations?

What follows are policy solutions for retooling America’s welfare program with a focus on economic mobility. These solutions allow the nation to learn from the experience of the past 20 years; yet, they reflect the reality of America’s 21st century economy, the needs of employers, the needs of prospective employees, and the needs of children.

1. Focus on Employment, Earnings, and Retention

The current TANF system is based on an imperfect federal performance measure — the work participation rate — that measures how well states engage families receiving assistance in certain work activities. It does not demonstrate how many individuals receiving TANF become employed or whether they are doing the activities most likely to lead to employment. In fact, states can perform very well on the measure while doing a less than desirable job of getting individuals into the workforce. Federal requirements related to the work participation rate create a disincentive for states to serve “hard-to-employ” individuals who may have any number of barriers to employment, such as health problems, disabilities, criminal records, drug addiction, or limited education. Rather, these requirements encourage states to focus their services on job-ready individuals or individuals who might not need as much assistance.

Some argue that any change to the work participation requirement is a step back from a commitment to the value of work. This is not the case. Moving instead toward measures that hold states and participants accountable to employment goals provides a much stronger commitment to work. States, programs, and participants should be focused on achieving three goals: 1) getting participants a job; 2) ensuring that earnings are sufficient to help participants get ahead, through both wages and number of hours worked; and 3) preparing participants to sustain employment or advance to a better job.

In a redesigned system, employment would be the primary outcome of interest, as employment strongly influences the factors related to financial health, such as the ability to meet basic monthly expenses and the availability of emergency funds. A successful TANF program would engage local employers, fully understand their staffing needs, and help participants develop skills that are in greatest demand. In addition, a premium would be placed on the development of jobs through subsidized employment and career pathway programs. With subsidized employment, public funds are used to create or support temporary employment for an individual who would otherwise be unemployed. Employers are typically expected to attempt to retain the individual once the subsidy is no longer available. Subsidized employment programs have a dual effect on the economy by employing an individual with a meaningful wage and by assisting small and medium-sized businesses to grow. For example, employers who want to expand their workforce but need financial support to take on the risk of an additional expense or a new employee benefit from the employment subsidy. In the career pathways model, TANF participants receive a basic education while also learning the skills needed for a specific job or industry. In this way, the model engages community and technical colleges, training individuals for careers in such fields as health care, early childhood education, and manufacturing.

The late Senator Edward Kennedy asserted on multiple occasions that “if you work 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, in the richest nation in the world, you should not have to live in poverty.” However, recent analyses demonstrate that wages, especially for low- and moderate-income workers, have stagnated nationally. In many states, a single-parent household with two children would be ineligible for assistance through TANF, even if they are only earning the federal minimum wage ($7.25/hour), working 40 hours a week, every week of the year. Such employed individuals may still need some form of public assistance, such as food assistance or the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), to make ends meet. Yet, even with these economic supports added to their earnings, such a family still cannot meet their basic monthly expenses.

What’s more, getting a job, even a good paying job, is not enough to move out of poverty if it is temporary or if a worker is unable to succeed in it. Because the current work participation requirement counts activities that may or may not lead to sustained employment, it rewards short-term, unsustainable work for too many participants, such as temporary or seasonal jobs. A new focus on retention and advancement would create incentives for states to support families with services that smooth their transition to permanent employment, such as assistance with child care, transportation, health care, or stress management, all of which can affect a new employee’s ability to keep a job. A system that supports participants for a reasonable period after hire could help stabilize an individual in a new job, benefitting both the employee and the employer. Such a focus on retention would reward states that help participants find permanent employment.

2. Expand Access to Job Training, Vocational, and Postsecondary Education

During the 1996 welfare reform debate, Senator Phil Gramm of Texas said the following about work and education:

Work does not mean sitting in a classroom. Work means work… Ask any of my brothers and sisters what ‘work’ meant on our family’s dairy farm. It didn’t mean sitting on a stool in the barn, reading a book about how to milk a cow. ‘Work’ meant milking cows.2

Yet it is a false distinction to say that work and education are mutually exclusive. There are many models that combine the concepts of work and education successfully. Cooperative education combines the two by delivering practical work experience with study. Community colleges, with their responsiveness and flexibility to local business, exemplify the idea that work and education are very closely linked.

Following the passage of PRWORA, there was a swift reduction in college enrollment among welfare participants. Nationally, there was an approximately 20 percent decrease in the college enrollment of all welfare recipients over the first two years of TANF.3 This mass exodus from college jeopardized the ability of these individuals to climb out of poverty, especially in a twenty-first century economy. A 2010 study found that, nationally, fewer than 8 percent of “work-eligible” adult TANF participants were engaged in education or training activities. Although these activities do increase the average earnings and overall incomes of families in the short-term, research has demonstrated that only former participants with at least a two-year postsecondary or vocational degree are likely to escape poverty by earnings alone. This research reveals a standard for education and training, attached to the goal of moving out of poverty, that is not supported by the TANF legislation itself.4 In addition, a study of six states found that 87 percent of former welfare participants who graduated from two- or four-year colleges were still off welfare six years later.5 Such research underscores the relationship between work and education and provides an illustration of what is possible when adopting a long-term lens focused on eliminating poverty.

The PRWORA sets forth 12 categories of work activities that can count toward the work participation rate, with the parameters for each activity defined by federal rule in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Among these, nine are considered core activities that count toward any hours of participation, and include activities such as employment or on-the-job training. However, three non-core activities — job skills training directly related to employment, education directly related to employment, and satisfactory attendance at secondary school or in a course of study leading to a GED — only count if the individual also participates in core activities for at least 20 hours per week (30 hours for two-parent families).

In a redesigned system, more participants would be able to access education and training activities, along with sufficient time, that would allow them to gain the credentials and skills needed to obtain living wage jobs. Yet, education and training would not be an open-ended activity. Instead, the amount of time an individual spends in such an activity would allow participants to achieve proficiency in a skill, trade, or career that meets the needs of the local labor market and moves them out of poverty.

In Colorado, jobs that have high projected growth rates and openings, and typically offer a living wage, include health care, information technology, construction and extraction, and business and finance. The vast majority of these jobs expect some level of formalized postsecondary training or education.6 Nationally, by 2020, 65 percent of all jobs in the economy will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school.7 It is clear that failing to prepare individuals to meet the needs of the local labor market, in a twenty-first century context, leaves the economy behind as well.

TANF programs would be required to work with postsecondary and vocational education systems to develop career pathways that meet the needs of employers. This necessitates a view of employers as essential to the work of helping vulnerable individuals gain stable, living-wage employment. Furthermore, nontraditional job training opportunities would be expanded and made available for welfare participants to enhance their ability to move into living wage jobs. In this way, the focus of the system moves from compliance and process to income and employment outcomes that truly lead to financial health and economic mobility.

3. Mitigate the Cliff Effect

Currently, working parents who experience wage growth may reach a “cliff,” where if they surpass a certain income threshold they lose eligibility for other public assistance, such as child care subsidies, food assistance, health care coverage, and tax credits. The net effect of a 20-cent per hour raise (or $416 per year) can result in the loss of thousands of dollars in work supports. To avoid this cliff, many individuals decline wage increases, overtime, increased hours, or career advancements. The cliff effect has become TANF’s new handcuff to poverty.

In this redesigned system, participants who become employed or earn increased wages would transition gradually from government work supports. A tiered benefit approach that allows individuals to improve their earnings and their careers while progressively moving off publicly funded benefits allows for greater economic mobility. The Affordable Care Act moves policy in this direction by providing health care subsidies for working people until they can earn a sufficient income to obtain health insurance without a government subsidy. Child care assistance, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), TANF, and other public benefits should follow a similar course.

4. Emphasize Money Management and Encourage the Accumulation of Wealth

For many people living in poverty, getting a job is the first time they have ever had a steady source of income. Many are not banked, or are underbanked, and have limited knowledge of investments, savings, or money management. In fact, the Office of Inspector General reports that one in four U.S. households lives at least partially outside the financial mainstream, and the average underserved household spends $2,412 each year on interest and fees for alternative financial services.8 Yet, receiving temporary cash assistance, or getting a job, is not simply about having money; it also requires the ability to manage money. By focusing on financial capability as part of a redesigned system, people can gain confidence in their own ability to plan for their financial future and to weather the next crisis. This will serve as a long-lasting benefit to their health and well-being over time. The TANF system could also create incentives for people to take positive steps toward financial behavior change, such as opening an account and saving in a financial institution, checking a credit report, or establishing a monthly budget.

In this redesigned system, services that build financial capability would be provided alongside cash assistance. Participants would be strongly encouraged to form a relationship with a financial institution by opening a transaction account, receiving their cash assistance through direct deposit, and obtaining a savings account. An incentivized savings program could help people to establish initial savings for a rainy day fund. Credit-building products and counseling services could be integrated to help ensure that credit scores are not getting in the way of job placement, or that poor credit is not inhibiting people from financing a car they need to get to work. Financial coaches who work alongside the other supportive structures (such as job coaches that some agencies deploy; see Michael Rubinger’s essay in this volume) help clients with setting and achieving financial goals, which will help to build confidence in changing financial habits over time.

5. Remove Asset Limits at the Federal Level

Exaggerated rhetoric surrounding welfare abuses, such as the “welfare queen” accused of enjoying a lavish lifestyle or bank accounts full of cash while receiving public assistance, led politicians to establish and strengthen asset limits. To qualify for public assistance, including TANF cash assistance, individuals or families must have financial resources, or assets, below a set limit, which provides a disincentive to many of the activities suggested in the previous section. Many low-income families are forced to spend down their existing assets to meet these limits and qualify for needed assistance. Asset limits prevent welfare participants from building basic wealth — a dependable car, a home, or savings for a child’s education. These are all necessary components for achieving economic independence and moving into the middle class. These very assets can lead the working poor to approach another cliff, similar to the income cliff, which serves as another handcuff to poverty. The current public assistance system forces families into an awful dilemma of choosing between saving money or staying on TANF for its much needed short-term support. While our public assistance system is meant to provide for families when they need it most, asset tests discourage saving and asset accumulation, the very actions that lead to financial health and well-being.

In this redesigned system, federal lawmakers would eliminate asset limits. At present, states can set their own asset limits. Many states, including Colorado, have already removed asset limits, providing a model for federal reform. Removing asset limits allows families to obtain the assistance they need, while helping them to save for the future. Overall, to truly lift families out of poverty and allow them to achieve greater economic mobility, national policy must not be punitive and it must focus on asset building as much as it focuses on income support.

6. Ensure Quality Child Care and Early Learning Opportunities for Working Participants

For parents to enter and stay in paid employment, child care is an essential work support. However, PRWORA eliminated the guarantee of child care for welfare participants trying to move into employment, leaving it to individual states to determine whether, and for how long, participants and former participants receive subsidized child care. Many of the jobs that parents obtain require a patchwork of care — part-time, before school, after school, evening, swing shift, and weekends. Parents blend formal care with family, neighbors, and sibling care — arrangements that frequently break down and can be unsafe for children.

Child care without quality is a missed opportunity. More than 50 years of research confirms that children from low-income families with high-quality child care do better on a range of socioeconomic and health outcomes in both childhood and adulthood compared with their counterparts who do not have the same experience. Investments in high-quality child care lead to some of the best returns on investment that exist in the public sector. There is also an opportunity to help children overcome the educational achievement gap that so routinely correlates with living in poverty.

In this redesigned system, working parents eligible for public assistance would have access to and incentives for selecting high-quality child care and early learning opportunities for their children. Colorado House Bill 14-1317, passed in 2014, modifies the state’s subsidized child care program, the Colorado Child Care Assistance Program (CCCAP), and aims to provide affordable, high-quality child care for working participants. Colorado HB14-1317 was created with the belief that affordable child care is necessary to support working parents’ efforts to find and keep good jobs, advance in their careers and education, and attain financial health and well-being. It further recognized that child care was as much about the child as it was about the working parent, creating statewide supports and incentives to parents and child care providers to expand high-quality access for low-income families. Provisions of the legislation include:

- Eligibility that includes job seekers and those enrolled in postsecondary education or workforce training so that child care concerns do not inhibit efforts to attain a better livelihood;

- An income eligibility structure that allows working families to afford child care despite minor increases in wages, thus lessening the cliff effect that deters families from earning a better wage;

- An allowance for child care beyond a parent’s exact hours of work, which encourages consistent, regular care;

- A tiered reimbursement system for child care providers such that those who are rated more highly on the state’s quality rating and improvement system receive a higher rate of reimbursement;

- A reduced co-pay for parents who choose a more highly rated child care provider on the state’s quality improvement and rating system.

In less than one year, Colorado has increased the percentage of children in CCCAP who receive high-quality care by approximately 10 percent.

Conclusion

Welfare policy in the United States needed a change in the 1990s. AFDC, a well-intended policy of a foregone era, became a restraint to economic mobility and paths out of poverty. PRWORA and TANF set out to transform a system that was not working as intended. Although this landmark legislation and program were highly successful at moving Americans off welfare, it failed to create a new path to economic prosperity, especially for America’s children. To build this new path to economic prosperity, honest debate and courage from political leaders is required. American families need a public assistance system whose safety net bridges the gap between getting back on one’s feet and building the financial foundation necessary for economic security and mobility. We must challenge ourselves to develop a new approach for a new economy, focused on eliminating poverty instead of eliminating welfare enrollment.

At the PRWORA signing ceremony, President Bill Clinton also stated, “This is not the end of welfare reform, this is the beginning.” We should continue to evolve our efforts in ways that build the economy, support new strategies related to financial health and well-being, and move Americans out of poverty. Such efforts will set a new direction for helping the poor to overcome poverty through meaningful work and economic mobility, achieving a future where all Americans have the greatest opportunity for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- H. J. Karger and D. Stoesz, American Social Welfare Policy: A Pluralist Approach (New York: Pearson Education, 2006).

- The Family Self-Sufficiency Act, #473, 104th Congress Congressional Record (September 11, 1995).

- National Urban League Institute for Opportunity & Equality, “Negative Effects of TANF on College Enrollment.” Special Research Report (SRR-01-2002). (Washington, DC: June 2002).

- Betty Reid Mandell, “The End of Welfare as We Knew It,”New Politics (October 2011).

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, “Chairman McDermott Announces Hearing on the Role of Education and Training in the TANF Program.” Press release, April 15, 2010.

- Colorado State Legislature, “The Colorado Talent Pipeline Report” (January 2, 2015).

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl, “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020” (Washington, DC: Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University, June 2013).

- Office of Inspector General, “Providing Non-Bank Financial Services for the Underserved.” Report No. RARC-WP-14-007. (Washington, DC: U.S. Postal Services, January 27, 2014).