How the Road to Financial Security is Paved with Financial Capability

Written by Andrea Levere, Prosperity Now (formerly CFED); Leigh Tivol, Prosperity NowAt CFED (the Corporation for Enterprise Development), we often joke that our parents don’t understand what it is we do for a living. “Expanding economic opportunity” — okay, sounds nice, but what does that mean?

The truth is, it’s complicated. Poverty is complicated. Inequality is complicated. And if we have learned anything over the years, it’s that there is no silver bullet, and we have a long way to go to find effective solutions.

And yet we believe that we are on the right track. During the past few decades, the community of people and organizations who care about these issues has grown exponentially. We have learned from experience, and we have not been afraid to try new ideas, even if they have not all worked quite as we imagined. Today, we stand together on the verge of a new era — an era of financial capability — that represents a more holistic, sophisticated, cross-sector, and data-driven set of approaches to help people and their families achieve lasting financial well-being. This opening chapter of What It’s Worth traces the path that has brought CFED and the field to this point, envisions the road ahead, and sets the stage for the thoughtful and provocative ideas, evidence, and opinions voiced by our fellow authors in the chapters that follow.

The Problem: Growing Financial Insecurity in America

Decades ago, few would have anticipated the dramatic increase in the complexity of the American economy, financial systems, and social safety nets, or how that complexity would transform the economic lives of individuals and families. Today, nearly every aspect of American life, from employment to housing to the generational transfer of wealth (and poverty) is tied to financial systems and other institutional structures, such as the workplace. Although these systems and structures provide valuable benefits, including the democratization of credit and technology-driven cost savings in the delivery of products and services, they bring new risks to consumers as well.

The fact is, it’s hard to be a consumer of financial services these days. Anyone who visits the website of a major financial institution or drives through a busy street filled with billboards advertising check-cashers and payday lenders can appreciate the pace and extent of change in the financial services marketplace in recent decades. This increasingly complex marketplace demands corresponding savvy to navigate successfully.

Consider that 50 years ago, our parents or grandparents:

- Weren’t bombarded by tempting credit offers in the mail. Credit cards weren’t born until the 1950s, and not widespread until deregulation in the 1980s. Today, more than 70 percent of Americans have at least one credit card, and the typical borrower carries nearly $10,000 in revolving debt (including debt from credit cards, private label cards and lines of credit).

- Had never heard of an adjustable-rate mortgage. Homeownership rates expanded significantly during the last 100 years (from 46 percent in 1910 to 64 percent in 2013), thanks largely to the post-Depression launch of the 30-year mortgage. The 2000s brought experimentation with the mortgage market — and in some cases, overtly predatory actions — that stripped the wealth of millions, especially households of color and those of lower income. Former FDIC chair Sheila Bair, writing in 2012, observed that as a result of “reckless” mortgage lending practices, “five million families have already lost their homes, an even greater number are still at great risk of foreclosure, and nearly a fifth of mortgage holders owe more than their homes are worth.”

- Did not fear that a single unpaid bill might torpedo their credit score. The use of credit scores as a “screen” has a profound effect on financial security in light of the fact that more than one-half of all consumers currently have subprime scores; tens of millions more are outside the credit mainstream because of “thin” or nonexistent credit files; and millions of consumers do not regularly check their credit scores. Without a good credit score, obtaining access to capital is difficult, expensive, or impossible.

- Likely had greater access to a mainstream or lower-cost financial institution. Between 1984 and 2011, more than 15,000 banks exited the industry; of these, about one-half merged with another bank, and one-third consolidated with other charters within their existing bank holding company. Bank branches have been steadily closing. The FDIC reports nearly 5,000 closures between 2009 and 2014. At the same time, high-cost “fringe banking” services have proliferated, particularly in poor communities and communities of color. Although usury is certainly nothing new, its scope and scale (and the devastation left in its wake) have reached new heights in the last few decades. In 2014, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reported, “Today, there are approximately 20,000 storefront lenders… By comparison, in 2012, there were 14,157 McDonald’s restaurants in the United States.”

Of course, all of this was happening while two other developments were making people even more dependent on this complex financial system: skyrocketing student loan debt, and the demise of the defined benefit plan/pension and subsequent reliance on individual retirement accounts, such as the 401(k).

The steady rise in the cost of public and private higher education, coupled with growth of for-profit educational institutions, has created unprecedented levels of student debt. The Brookings Institution found that in 2000, the average student borrowed only 38 percent of net tuition costs (or about $3,600) to finance his or her tuition. Ten years later, that figure had risen to nearly 50 percent (or $5,500).

With the decline of the defined benefit pension, retirement income became much less a benefit of one’s job and much more a personal responsibility. In 1978, Congress passed legislation that enabled Americans to save through tax-sheltered work contributions. The major role of employers was to establish these programs, advertise them to employees, and at times offer a match. Yet many companies failed to set up these programs, and too many employees with the option to save did not sign up. Today, numerous studies estimate that more than one-half of employees, and perhaps as many as two-thirds, have inadequate savings to support themselves in retirement. One analysis suggests that one-third of current workers aged 55 to 64 will have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line once they retire. In his book The Great Risk Shift, Yale professor Jacob Hacker documents this trend of public and private institutions passing economic risk to consumers under what he describes as the guise of “personal responsibility.”

Mainstream sources of financial stability — long-term job security, the defined-benefit pension, the neighborhood bank — are fast disappearing. These factors have been accelerated by the reality that achieving the American dream has become more elusive for the majority of the nation. A high school education is insufficient to achieve a sound middle-class existence. Our financial relationships and access to financial products increasingly occur online or through an unfamiliar agent on a customer service phone line. Personal integrity is no longer sufficient collateral to secure a loan or get a job.

In addition, inequities by race, class, and gender are becoming even more apparent in the widening income and wealth gaps between the haves and have-nots (see the essays in this volume by Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, José Quiñonez, Lisa Hasegawa and Jane Duong, Elsie Meeks, and Heidi Hartmann). We witness how the economic frameworks that create opportunity for some systematically deny it to others. Not only is the playing field not level, but the goalposts keep moving farther away. The lack of transparency in many financial products and the extent of predatory practices mean that financial decisions can have an outsized impact on consumers’ lives, especially when things go wrong, as they did so dramatically during the Great Recession.

The Solution: Create Economic Health at the Household Level for even the Poorest Americans

These increasingly risky financial and economic realities have shaped CFED’s work over more than three decades. We have sought to expand economic opportunity, reduce financial insecurity, and create wealth. We began in the early 1980s with a focus on promoting self-employment as a route out of poverty for low-income people. Virtually no one believed this was possible until we spent five years tracking American women on welfare who started their own businesses through the Self-Employment Investment Demonstration (SEID). We discovered that:

- Of the 1,316 welfare recipients who participated in SEID, 408 started businesses — a percentage roughly equal to the percentage of business owners in the U.S. economy overall;

- 79 percent of SEID businesses were still operating 2.6 years after starting;

- Six times the number of SEID business owners derived their primary income from their business after participation than before; and

- Reliance on Aid to Families with Dependent Children (cash assistance) and food stamps declined 65 percent and 62 percent, respectively, among business owners participating in SEID.

This experience taught us that low-income people have more capacity than opportunity, and that it was our responsibility to create on-ramps into the economy that provided the structure and incentives that all Americans need and deserve to succeed.

When we launched the American Dream Demonstration in the late 1990s to test the power of Individual Development Accounts (IDAs), which are savings accounts that receive additional dollars from government or philanthropy as a match, few policymakers or practitioners believed that low-income people could save at all. Even more disturbing was the critique that it was “unfair” to ask people who have too little money to begin with to save. What did we discover from this experiment? Not only did low-income people clearly demonstrate that they could save, but in fact, the poorest 20 percent of accountholders — with incomes less than 50 percent of the poverty line — saved at a rate more than three times that of the highest-income accountholders. They told us, essentially, that it was the price of hope. Otis, a saver at Capital Area Asset Builders in Washington, DC, summed it up: “When you first get your money, it is easy to spend it on dinner. But once you realize the money is for your future, you start to really save.”

This demonstration taught us many new things that influence our work today. Incentives, such as savings matches, matter — but not as much as we thought. Institutional arrangements, from direct deposits to peer counseling, mattered as much or more in helping the savers reach their goals of education, homeownership, or entrepreneurship. When financial education was paired with an account and savings goal, outcomes improved. Each hour of financial education, up to 10 hours, increased average monthly net savings by $1.16, or $139 per year, a substantial sum for families living near or below the poverty line.

Yet while IDA programs were clearly transformative for many, these programs also revealed that not all low-income households were ready to save for a long-term asset. How could we help them get there? After all, if households, particularly those of low and moderate income and households of color, lack access to the information and skills to make sound financial decisions in an increasingly complex environment, they are likely to find achieving economic security elusive at best, and impossible at worst.

Knowledge Is Power: The Faith in Financial Education

By the 1990s, Americans had latched onto the idea of financial education as a response to these new financial realities. Educators, employers, bankers, and policymakers alike supported financial education programs as a seemingly simple solution to the financial challenges faced by low-income consumers. If people just had more information, the thinking went, they would be able to make wiser financial decisions.

In the 1990s and 2000s, there was enormous growth in financial education programs and initiatives in every sector. Federal financial education commissions and advisory councils sprang up. Hundreds of curricula were developed, including the widely used FDIC Money Smart materials, as well as a multitude of teaching and learning materials created by nonprofits and for-profits alike. Foundations invested millions in supporting financial education programming in every corner of the nation. States began to require it in schools. Financial education was, in short, a hot topic.

Banks furthered this trend for several reasons. Many saw it as a good business development tool, a way to get new customers in the door. In addition, banks offering financial education could receive Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit by providing services in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. And financial education also represented a new tool in the arsenal for managing credit risk among borrowers who were increasingly taking on additional debt.

Finally, financial counseling was integrated into federal programs that involved use of credit or other financial products, especially homeownership programs. In addition, IDA programs mandated general financial education and offered additional asset-specific training as incentives to promote homeownership, entrepreneurship, or postsecondary education.

Enhancing Financial Education with Wealth Creation Strategies

At the same time, another significant influence was at play: the growing emphasis on helping low-income households build not just income, but wealth. Beginning with Michael Sherraden’s seminal 1990 book Assets and the Poor, asset building emerged as a strategy for helping families escape poverty. Whereas traditional approaches to poverty alleviation emphasized increasing income, this newer research recognized that income is necessary but insufficient. Assets — a home, savings, an education, or a business — must accompany income to help families move up the economic ladder. Assets create a financial buffer to weather emergencies, promote success in the labor market, inspire long-term thinking and planning, and enhance the economic and psychological well-being of individuals and their families. An entire field of practice, policy, research, product innovation, and philanthropy has developed in the asset-building space over the past 35 years.

At the heart of the asset-building field is a simple premise: Given the right frameworks and incentives, people will save, regardless of income, and move toward asset ownership. From the start, practitioners experimented with and adopted as a best practice the integration of asset-specific and general financial education into their programs, with the added element that the education was tied directly and continually to the promotion of specific behaviors and actions.

One powerful measure of how much the asset-building field has grown in just the last decade is captured by the growth in partners for CFED’s Assets & Opportunity Scorecard, the nation’s most comprehensive benchmarking tool in how well state governments build and protect assets for their residents. When CFED released the first edition of the Scorecard in 2003, we partnered with just five organizations — which was the number of state organizations with a mission of building assets for low-income Americans. The number of partners grew and by 2012, CFED organized a group of advocates, practitioners, policymakers and others — the Assets & Opportunity Network — to connect the growing number of state, regional, and local organizations dedicated to expanding financial capability and opportunity. Today, this Network represents 1,840 members, whose work has connected financial education with building financial security and assets, and redefined how these two efforts worked together.

Yet in the early years of the new century, as the recession loomed and student debt and foreclosures continued to mount, it became clear that neither financial education nor asset building were enough to improve economic stability and well-being for large numbers of families. Michael Sherraden, whose voice carries great weight in the field, acknowledged with Ray Boshara in 2008 that financial education does not necessarily translate to a direct path toward savings and asset accumulation. By that time, others in the field had also begun to question the impact of financial education programs. Many programs included no evaluation of their efforts at all, and for those that did, the evidence of effectiveness was spotty. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) noted in 2013 that “while some of these programs … show promising results, overall there is limited systematic evidence to tell us about the most effective ways to improve consumer knowledge and decision making about personal finances.”

At the same time, many stakeholders who had long identified as asset-builders were recognizing that for some households, the goal could not be to buy a house, or start a business, or save for retirement — not yet. What these households needed first was a broader array of services: credit repair, a simple bank account, access to public benefits, plus the knowledge and know-how to navigate financial systems.

More Than Faith: The Rise of Financial Capability

Experience has taught CFED and the field that we must help people not just learn, but act. We must not only make sure that doors of opportunity are open, but that people walk through them. This understanding was the impetus for the birth of the field we now know as “financial capability.” The term itself first gained traction internationally and quickly took root in the United States. The Center for Financial Services Innovation succinctly describes the difference in both nomenclature and impact in its aptly titled 2009 report, From Financial Education to Financial Capability: Opportunities for Innovation, noting: “The shift in language is more than semantics. Financial education is a set of provider outputs; financial capability is a set of consumer outcomes” that make a difference in peoples’ lives — for instance, being able to meet monthly expenses, planning for the future, and choosing quality financial products.

As the notion of financial capability began to take hold, many in the emerging field were coming to another critical realization: that despite good products, good services, and the very best of intentions, many low-income households were not using the financial opportunities being offered. With apologies to Field of Dreams, we were building it, but they weren’t coming.

Practitioners and policymakers began to realize that part of the problem was that we were not listening to the customer. To use an entirely unrelated example: If we were McDonald’s and considering creating a new sandwich, there would be an enormous amount of thought put into how to develop, refine, and market that product to the consumer. Focus groups and pilot tests would ensue, and the new product would be designed and polished to within an inch of its life before it ever came close to hitting the streets. In addition, McDonald’s would use all the information it had about its customers’ behaviors to inform its decisions — their preferences, patterns, and psychologies, and what made them choose to buy (or not buy) one product over another. Yet the financial services field was charging ahead with little more than a notion that the approach should work.

That has begun to change in the past few years, with exciting applications of traditionally for-profit product development tools to financial capability products and services. The notion of human-centered design, which examines the needs, dreams, and behaviors of people who will be affected by a given product or program, is beginning to make a real change in how organizations design financial products and services for low-income individuals and families. Human-centered design has also prepared the field for the next leap — integrating behavioral science and economics into our work. The field now has a deeper understanding of what promotes or impedes “good” consumer behavior.

After all, at the end of the day, our goal is behavior change, to ensure that people make use of opportunities for financial security to better their financial position. To continue the Field of Dreams metaphor, the question becomes: If we build it, how do we make it as easy as possible for them to come and stay? In financial capability terms, this translates to strategies such as opt-out and automatic savings programs; thoughtfully designed incentives and rewards for desirable financial behaviors; and fewer barriers to achieving financial goals. For instance, where a financial education class might have simply offered information on where a person could open a bank account, financial capability programs would bring a banker to the class to open accounts on the spot and help participants set up direct deposit. This makes savings automatic and easy, in addition to providing direct access to a mainstream financial account with lower fees and interest costs than found with alternative financial services providers such as payday lenders or check cashers.

Tax time is when these innovations have been most rigorously tested. Tax season is the moment when low-income families often have the largest amount of cash, thanks to refunds from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Using core principles such as easy account opening, powerful incentives, and well-timed “prompts” or messaging, the SaveUSA program (sponsored by the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs Office of Financial Empowerment) tested treatment and control groups to see if these factors could encourage more savings at tax time. The results are convincing. Between 9 percent and 23 percent of the control group deposited some or all of their tax refunds. In contrast, 90 percent of the treatment group with access to a well-designed product saved.

Outcomes of similar magnitude have resulted from decisions by companies to switch from an opt-in to opt-out retirement savings program in which an employee must actively say no to an automatic deduction. Between 2003 and 2011, the percentage of companies offering opt-out 401(k) programs skyrocketed from 14 percent to 56 percent. An analysis from the National Bureau of Economic Research examined one medium-sized U.S. chemicals company that implemented automatic 401(k) enrollment for new hires and found that the plan participation rate was 35 percentage points higher after three months on the job than for “standard” enrollees, and remained 25 points higher after two years.

How Financial Capability Changed CFED’s Strategy to Build Wealth for Low-Income Americans

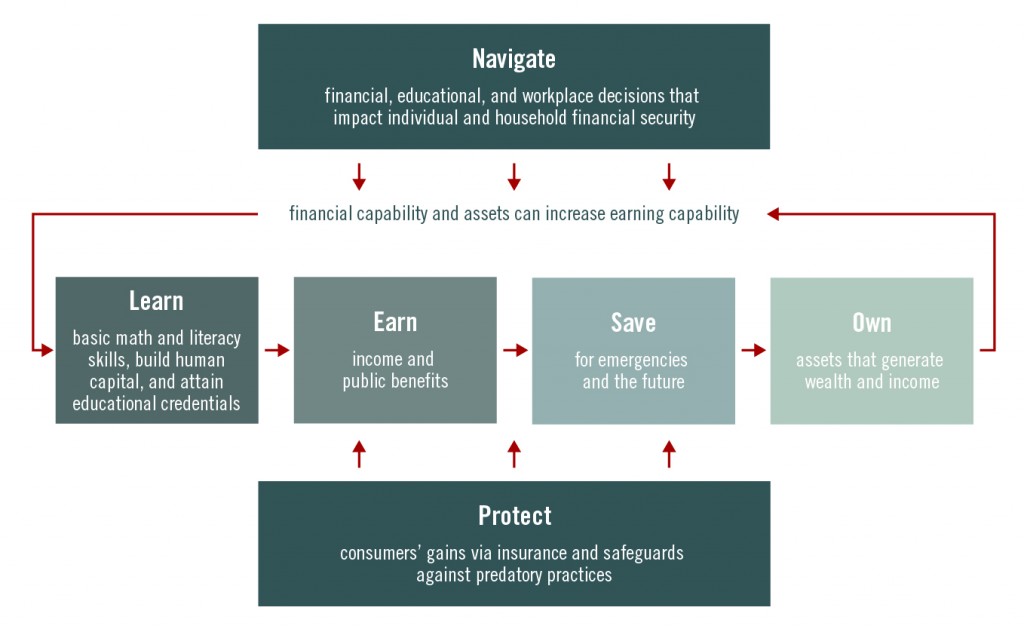

In many ways, CFED’s own experience in grasping the importance of the financial capability concept reflects the evolution of the larger field. In 2010, we realized that we needed a better way to capture the entirety of families’ financial needs, not just financial education and asset building. Our Household Financial Security Framework (see Figure 1) was an attempt to build household financial security over time. We began to think about reducing poverty and achieving financial security and empowerment as a dynamic process. Households gain financial management skills, build human capital, increase income, begin to save, leverage saving into assets, and protect gains made along the way. Households can engage this cycle at many places along the continuum; they also iterate and evolve their strategy over time.

The Framework describes the cycle of financial capability from the household perspective. Households need enough income to finance basic consumption and pay down debt with enough left over to save for the future. Once savings have accumulated, they can be invested in assets, which can then help households boost their incomes through increased earning capacity or income-generating dividends or profits. Throughout the cycle, access to insurance and consumer protections helps households protect their gains. This is an ongoing process in which each component contributes to the next, and to the household’s overall ability to become financially stable.

The development of the Framework was a turning point in the way we thought about our work. It gave us a way to weave a powerful, cohesive narrative about the many different and interconnected ways that could support the burgeoning asset-building field. It also allowed us to bring new, unexpected partners into our orbit, players who might touch only one part of the financial capability “cycle” but who represented important constituencies or vantage points. Suddenly, we had a tool that allowed a wide range of organizations — health, affordable housing, public safety, community development finance, education, employers — to see the specific ways their work contributed to the financial betterment of families.

We began to see more sectors concluding that financial capability was essential to achieving their own larger goals. For example, at a recent convening hosted by Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future (SAHF) — an organization composed of many of the most productive affordable housing organizations in the nation — Patricia Belden, President of POAH Communities, said: “If we want to improve the lives of our residents, we need to go beyond traditional property management and work with partners who can help our residents build credit, save for a home or college, or start a business. We want to give our residents the financial tools to help them to make their dreams for the future a reality.”

Financial Capability Gains Momentum

The Great Recession accelerated the adoption of financial capability as a concept by leaders in government, the social services sector, academia and the private sector, especially as financial insecurity spread to formerly middle class households. In 2010, President Obama created the first President’s Advisory Council on Financial Capability, followed in 2013 by a similar council focused on youth. Also in 2010, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Intended as widespread reform in response to the Great Recession, it established what would later become the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB seeks to “make markets for consumer financial products and services work for Americans” — a mission accompanied by greater emphasis on building financial capability coupled with enforcement powers when necessary. For the first time, we have a government agency charged with, among other things, ensuring that all Americans become more financially capable.

In less than five years, the design and delivery of financial capability services have been championed and incorporated into core lines of business in the public, nonprofit, and private sectors. With a growing body of research on the subject making the theoretical case for financial capability, and the successful experiences of “early adopters,” this new field began to flourish. Yet the job of building financial security for individuals, households, and communities is just beginning.

Four words or phrases describe the trends and practices that are expanding the field’s scale and impact today: integration, coaching, credit scores, and product innovation.

Integration

Growing numbers of government agencies, nonprofits, and for-profit businesses (especially employers) are embedding financial capability into their core programs and services. At the federal level, the departments of Treasury, Health and Human Services, Education, and Housing and Urban Development have each launched or begun to explore initiatives to integrate a range of financial capability strategies into their agencies’ service delivery programs.

Integration is even farther ahead at the state level. Delaware’s Stand By Me partnership, led by the state and the United Way of Delaware, locates financial empowerment centers within public agencies, nonprofits, employers, and educational institutions (see Rita Landgraf’s essay in this volume). In Colorado, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Education are planning a two-generation initiative that will embed financial capability services for parents into the state’s early childhood programming (see Reggie Bicha and Keri Batchelder’s essay in this book).

Cities have gotten into the game as well. In 2006, New York City launched the nation’s first municipal Office of Financial Empowerment to build financial capability among low-income families. Today, 14 major cities compose the Cities for Financial Empowerment Coalition, providing financial capability services to millions of people through innovative one-stop centers and community partnerships. As Greg Fischer, mayor of Louisville, KY (one of the Cities for Financial Empowerment) writes in his essay in this book, “We are developing an integrated, community-wide system… Leaders across multiple departments have embraced the goal of improving the financial stability of the residents we serve by promoting financial access, capability, and asset-building strategies.”

The nonprofit sector also began to blend financial capability into other services: offering assistance with workforce training and education; helping clients gain access to public benefits, tax credits, and financial aid; and offering financial education, counseling, or coaching, along with access to financial products and services. The Working Families Success Network is an example of this integrated approach and has more than 100 sites across the country. Section 2 of this book highlights examples of integration from multiple sectors, such as Skyline College’s on-campus SparkPoint Center, which provides services and resources to help students and community members achieve financial self-sufficiency (see Regina Stanback Stroud’s essay). The private sector is also beginning to incorporate financial capability strategies into employee benefits, such as Staples’ efforts to leverage financial games and new financial products like “myRA” to increase employee engagement with retirement savings (see Regis Mulot’s essay in this volume).

Financial coaching

One-on-one financial coaching is growing rapidly, with powerful results (see the essays in this book by Michael Collins, Michael Rubinger, and Rita Landgraf for more information). Such coaching helps consumers set goals, establish a plan of action, and change behaviors. Meeting people where they are, the main idea behind modern financial coaching, empowers participants and allows them to have ownership over their financial choices and behaviors. Unlike a quick class or workshop, coaching is a long-term relationship, helping people to organize and prioritize their financial needs, supporting them, holding them accountable to their self-determined goals, and monitoring those behaviors over time.

For instance, Destiny, a client with The Financial Clinic in New York City, wanted to pay down her substantial debt, and in the longer term, buy a car to help her more easily commute to her job. Through the coaching relationship, Destiny set a realistic budget, identified opportunities to save, and established an income-based repayment plan for her student loan. By the end of her first year in coaching, Destiny had already paid off a quarter of her debt, increased her credit score by 30 points, and saved $3,000, all while sticking to her budget.

Credit scores

A credit score plays a powerful role in determining everything from accessing credit to renting an apartment to securing a job. Not only must the methods of credit scoring today be made transparent, but we should also leverage the power of “big data” to develop alternative methods of creating meaningful scores. Such alternatives could bring tens of millions of “credit invisibles” — consumers without scores — into the credit system. The Credit Builders Alliance (CBA), for example, is helping nonprofit lenders report loan data to credit reporting agencies. In 2014, CBA released a study with Experian that analyzed outcomes for consumers, including credit invisibles, who opened credit products offered by CBA members. Over two years, 58 percent of these borrowers saw their credit score increase, and more than 20 percent moved to a lower risk category (i.e. from subprime to nonprime credit).

Product innovation

The design and distribution of safe, affordable, high-quality financial products and services, ranging from prepaid cards to new methods of credit scoring, are enabling consumers to match products not only to their specific financial needs, but to their desired financial behaviors as well. The FDIC Model Safe Accounts, which bring the underserved consumer into the financial mainstream with safeguards such as the elimination of overdrafts, is one of the most promising trends. In addition, the expansion of employer-based financial education or financial wellness programs and savings products — especially opt-out retirement programs — creates opportunities to reach millions with financial capability products and services. Finally, applying innovations from other sectors — such as leveraging the concept of lottery winnings into prize-linked savings awards as championed by Doorways to Dreams — combine the best in consumer marketing with proven wealth-building approaches.

How Financial Capability Promotes Financial Well-Being

As important as financial capability may be, it is not the end goal. Ultimately, we are aiming to improve the financial situation for families, narrow the gap between rich and poor, and increase the opportunity for all households to be financially well. This notion of “financial well-being” is the most recent advance in understanding how to build financial security and opportunity. It builds on what has been learned while offering a new framework that more accurately and effectively assesses the financial condition of a household.

In early 2015, the CFPB released four criteria to describe financial well-being. The list was developed through an extensive research effort with consumers themselves.

To be financially well, a person:

- Feels in control of his or her day-to-day finances;

- Has the capacity to absorb a financial shock;

- Is on track to meet financial goals, whatever those might be; and

- Has the financial freedom to make choices to enjoy life.

For the first time, we have criteria and a set of metrics to use in charting the road ahead (see Jennifer Tescher and Rachel Schneider’s essay in this volume for further discussion). Yet we also have the data that show us how far we still have to go. A dwindling set of American households can claim to meet the CFPB’s financial well-being criteria today. More than one-third of households have no emergency savings, and 44 percent do not have sufficient liquid assets to survive for three months in a fiscal emergency.

Additional CFPB research has identified key factors of financial well-being, including social and economic environments; available opportunities; and individual personality, attitudes, knowledge, and skills. All of these can affect consumers’ behavior in the financial realm, and their ultimate satisfaction (or lack thereof) with their financial situations. Some, particularly individual factors, are within a consumer’s control, while others, such as the socioeconomic climate, are not. The charge for practitioners and policymakers, then, is to help individuals make the most of the agency they do have, and to tailor their services and strategies accordingly. It also highlights where this work, which focuses largely on the individual or the household, intersects with place-based strategies of the community development field (see, for example, the essays in this volume by Angela Glover Blackwell and Paul Weech). The possibility of building new bridges between these two fields holds great promise.

In the same way that the subject of calculus weaves together many strands of mathematics, the notion of financial well-being combines many of the interventions that we have described in this essay. It starts with high-quality and culturally appropriate financial information. Financial coaches heighten the value and impact of this information by encouraging self-directed goal-setting and personal accountability. Yet individual effort is not, nor should be, enough. The lessons from behavioral economics, marketing, and policymaking affirm that the design of products and services, the delivery structures and platforms, and financial incentives and regulatory protections matter just as much as an individual’s actions in achieving financial well-being. In many ways, financial well-being captures the ultimate outcome that we’ve been seeking when we align people, systems, and policies towards a common goal.

“What It’s Worth”: Advancing Ideas, Sharing Experience and Changing Policy

The field of financial capability is young. But the rapid growth of interest and activity signals that it is addressing a vital need within our economy and society.

This book aims to accomplish three goals:

- Illustrate the realities of the financial problems and challenges faced by American households today (Section 1);

- Capture the enormous creativity and innovation underway in different sectors, institutions, and among policymakers to expand the content and delivery of financial capability to serve different markets and needs (Section 2); and

- Point to next steps in research, policy, and practice across all sectors — public, private, and social — to implement both proven and evolving solutions so we can all live a life of financial well-being.

What It’s Worth reflects a diverse range of voices. Authors include public health professionals, policymakers, college presidents, bank regulators, economists, and nonprofit leaders who all agree that our financial lives matter. Although the authors approach the topic grounded in their unique backgrounds and experiences, each articulates why financial health and well-being matters to them and the work they are trying to achieve.

The book affirms that this is a universal issue that affects all of us, although not in the same ways. It is not an “us” versus “them” topic; we all can understand, sometimes in a deeply personal way, the challenges and opportunities met while striving for a sense of financial well-being. It presents solutions both practical and strategic to ensure that both practitioners and policymakers can work in concert to set people on the path to financial well-being. We look forward to collaborating with you on this journey.

The authors express deep appreciation to Christopher Bernal of CFED for his research assistance.

NOTES

- Gallup, “Americans Rely Less on Credit Cards than in Previous Years” (April 25, 2014).

- CFED, “Assets and Opportunity Scorecard, Average Credit Card Debt” (2014).

- U.S. Census, Historical Census of Housing Tables – Homeownership (October 31, 2011); CFED, “Assets and Opportunity Scorecard, Homeownership Rate”(2013).

- Sheila Bair, “Foreword.” In The State of Lending in America and Its Impact on U.S. Households, edited by Debbie Bocian et al. (Washington, DC: Center for Responsible Lending, 2012).

- CFED, “Assets and Opportunity Scorecard, Main Findings” (2015).

- Michael A. Turner, Patrick Walker, and Katrina Dusek, “New to Credit from Alternative Data” (Durham, NC: PERC, March 2009).

- Anne Kim, “What’s Your Number? Credit Scores and Financial Security” (Washington, DC: CFED, 2013).

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “Community Banking Study” (Washington, DC: FDIC, December 2012).

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Payday Loans: Time for Review,” Inside the Vault (Fall 2014).

- Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney. “Rising Student Debt Burdens: Factors Behind the Phenomenon.” (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, the Hamilton Project, July 5, 2013).

- Teresa Ghilarducci, Joelle Saad-Lessler, and Kate Bahn, “Are U.S. Workers Ready for Retirement? Trends in Plan Sponsorship, Participation, and Preparedness,” Journal of Pension Benefits (Winter 2015): 25–39.

- CFED, “Downpayments on the American Dream Policy Demonstration (ADD),” Common Progress Report (Spring 2001).

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FDIC Money Smart Survey of User Organizations, 2003 to 2004 (Washington, DC: FDIC, 2004).

- Michael Sherraden and Ray Boshara, “Learning from Individual Development Accounts,” in Overcoming the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Financial Education and Saving Programs, edited by Annamaria Lusardi (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 264–283.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Feedback from the Financial Education Field” (Washington, DC: CFPB, May 2013).

- Josh Sledge, “From Financial Education to Financial Capability: Opportunities for Innovation” (Chicago: Center for Financial Services Innovation, March 2010), 5.

- IDEO, “Human-Centered Design Toolkit, 2nd Edition” (San Francisco: IDEO, July 2011), 18.

- Rachel Black and Elliot Schreur, “Connecting Tax Time to Financial Security” (Washington, DC: New America Foundation, February 2014).

- Richard Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi, “Behavioral Economics and the Retirement Savings Crisis,” Capital Ideas (Summer 2013).

- John Beshears et al., “The Importance of Default Options for Retirement Saving Outcomes: Evidence from the United States.” In Social Security Policy in a Changing Environment, edited by Jeffrey Brown, Jeffrey Liebman, and David Wise. (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009).

- Financial Clinic, “Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2013” (2013).

- Credit Builders Alliance, Analysis of CBA Members: Confirms Value of Credit Building, August 2014.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Financial Well-Being: The Goal of Financial Education” (January 2015).

- NeighborWorks America, “One-in-Three U.S. Adults Has No Emergency Savings Despite Improving Economy.” Press release (March 31, 2015).

- CFED, “Assets and Opportunity Scorecard, Liquid Asset Poverty Rate” (2011).

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Financial Well-Being: What It Means and How to Help” (2015).